THE CRAFTS

OF KUTCH

Kutch’s craft industry is composed of over twenty one craft livelihoods. Craft is a living creative industry made from the hands of skilled artisans and generations-old tradition.

About Kutch

Kutch is known for the colorful silken threads that decorate traditional Kanchlies and Kanjaries worn by Kutchie women. Embroidery is the most visible and recognized craft in Kutch. More than 40 styles of embroideries color the region, representing Kutch’s diverse cultures, communities, and landscapes. Color and craftsmanship are not limited to Kutch embroideries. There are over 20 other textile and non-textile craft sectors which constitute artisans’ primary source of income.

For generations, Kutch has been home to nomadic communities whose traditional work of animal husbandry and craft have lent to each other forming a rich economic and cultural tapestry. Today, Kutch is a confluence of various art, craft, and music forms. Migration brought the distinctive elements of craft traditions from Sindh and Northern India to Kutch. These elements, inherited skill, and community identity are deeply imbedded in the region’s craft culture. Until three decades ago, each craft’s production process, from the sourcing of raw materials to the sale of finished products was practiced within the artisans’ communities.

While craft constitutes the second largest sector of the Indian economy (second only to agriculture), in Kutch, craft and agriculture are parallel economies. Unfortunately, many natural disasters have denigrated Kutch livelihoods. The steady erosion of the region’s primary productive assets (land and cattle) has resulted in an increasing dependence on craft as livelihood. This dependence coupled with limited access to raw materials and markets has resulted in the vulnerability of Kutch artisans and their craft traditions.

In 2001, a massive earthquake shook the region, resulting in a significant loss of life and widespread destruction. The earthquake’s impact on craft livelihoods was devastating. Those most affected were artisans who lost their asset base – work sheds, tools, equipment, and local markets. Quake related losses and shifts in markets and culture challenged the future of Kutch craft. The inherent strength of the Kutchie spirit focused local energy on collaboration and efforts to rebuild. Craft remains the primary source of income for artisan families. The traditions which have colored the region for centuries continue. Each craft sector faces new challenges and opportunities, which must be addressed for the future of Kutch craft and the livelihoods of 60,000 artisans.

Hand Embroideries

of Kutch

PAKKO

Pakko embroidery is practised by the Sodha and Jadeja communities. Pakko embroidery gets its name from an essential characteristic that defines it. Pakko means solid, strong, and this is the defining feature of this style. The solid compactness is achieved mainly through an abundant use of the tight, open and elongated chain stitch known as the cheereli saankdi. This stitch is used, along with a few other stitches, to create floral, animal and bird motifs.

Craftswomen use mirrors and the khann — a single unit of the chain stitch — to lighten the density of Pakko embroidery. The khann also works as an effective highlighter.

NERAN

Neran embroidery gets its name from the Kutchi word for the ‘eye’ — neran.

A tiny, eye-shaped unit serves as the building block. Each unit is outlined in a dark colour, filled in with a bright colour and highlighted in white. Small-sized mirrors are used in creative ways to enhance the appeal of this embroidery.

Traditionally, Neran embroidery used to be a small component of Pakko embroidery. In recent times, craftswomen have recognized the enormous potential of Neran. They now acknowledge it as an individual embroidery style that has a distinct identity and its own language of stitches, colours, motifs and designs.

Neran embroidery is practised by the Sodha and Jadeja communities.

AHIR

Ahir embroidery is practised by the Ahir and Meghwaad Gurjar communities.

Ahir craftswomen use the word thassa to define their embroidery. The word suggests a confidence, a boldness that celebrates abundance and opulence. Indeed Ahir motifs are large and colourful, the embroidery lush, dense and chock-a-block with mirrors. The combination of these elements creates a vibrant embroidered universe full of flowers, birds and animals – a reflection of the predominantly agricultural lifestyle of these two communities.

Ahir embroidery is open to innovation. Non-traditional elements such as abstract motifs, muted colours and minimalist designs have also been seamlessly integrated. But always the core Ahir values are respected, as evident in the use of specific stitches for specific functions: the small, round saankdi or chain stitch to outline the motifs; the vaano, the herringbone stitch, to fill in; and the daano, a single chain, or the bakhiyo, the backstitch, to highlight and provide the final flourish.

NODE

The Raau Node community practises six different embroidery styles.

The small, isolated Raau Node community is spread over just a handful of villages in the remote areas of Banni and Pachcham that fringe the salt desert. Despite the isolation, or perhaps because of it, Node craftswomen have created a distinctive style characterized by big, bold, colourful designs, large mirrors and floral-inspired, predominantly circular motifs. All the elements are densely embroidered and create an embossed effect that is easy to identify as Node.

RABARI

Rabari Embroidery

Dhebaria Rabari Applique + Embroidery

The Rabari community has several subgroups, each with its own style of embroidery.

Irrespective of subgroup, Rabari men and women lead a nomadic life in search of pasture with their sheep and their camels. Often it is the women who lead camel caravans through scrubland full of thorny shrubs.

Rabari embroidery styles are bold and vigorous. They use the elongated chain as the main stitch to create large, stylized motifs of birds and animals. Thus vibrantly coloured, abstract renditions of camels, peacocks, scorpions and even elephants are found in Rabari embroidery. The natural world also finds expression in the form of thorn-like highlights that are ever-present around the motifs.

The abundant use of mirrors of different shapes is yet another distinctive feature of Rabari embroidery.

DHEBARIA RABARI APPLIQUE+EMBROIDERY

While the embroidery stitches of different groups of Rabaris are more or less similar, the Dhebaria Rabaris have a unique style of applique + embroidery freehand designs that have bold and colorful motifs. These are done by each artisan as per her imagination without any graph or stencil print design to follow, making each piece unique. Their motifs are inspired by their culture and what they find around them – such as Kavadiyo (a man who carries heavy weight balanced on two sides of his shoulders with a bamboo) – referred in traditional applique, embroideries to a legendary person called Shravan, who is said to have carried his parents on a kavad for pilgrimage, butta suda (a pair of parrots), vichchhu (scorpion), kukda (hens), morlo (peacocks), hathido (elephant), chakli (sparrow), kubo (shrine), ambo (mango), fuldo (flower) etc.

SOOF & KHAARAK

Soof

Khaarak

The Meghwaad Maaru community is best known for its two counted thread embroidery styles called Soof and Khaarak. In counted thread embroidery, there is no outline or drawing done on the fabric to guide the craftswomen. Instead, the design is conceptualized by counting the threads of the fabric and mentally working out the composition.

Soof embroidery uses a single stitch to create complex geometric designs. It is one of the most challenging styles to render. The recent innovation of using circular mirrors adds yet another dimension of complexity.

Soof embroidery is worked on the reverse side of the fabric. When turned over, the front displays embroidery that is so fine that many mistake it for machine embroidery and have a hard time believing that such precision and perfection is the work of the hand.

Khaarak embroidery style gets its name from khaarek, the Kutchi word for the date fruit. It features simple as well as complex geometric forms.

Craftswomen begin by plotting the squares and rectangles that constitute the grid of the geometric forms. A dark colour is used to outline the grid. Spaces within the grid are filled in using the satin stitch in different colours. Mirrors provide the final flourish.

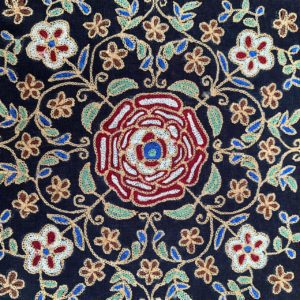

AARI

The Mochi community practises Aari embroidery.

Renowned for its subtle, painting-like effect, this style dates back to Mughal times and beyond, when male artisans were commissioned by royalty to create this embroidery exclusively for them. Aari continued to enjoy popularity during the British Raj, when the European elite took the place of maharajas and princes as its patrons.

Today Aari embroidery is practiced in many parts of India, including Kutch. It is done with a hooked needle called the awl, on lightweight fabrics that are stretched over a wooden frame. The painting-like effect is achieved through the exclusive use of a very fine chain stitch, moving gently from darker to lighter shades or from lighter to darker of the same colour. The Mughal influence still lingers in the floral motifs and the occasional use of gold and silver threads.

Jat

Jat-Garaasiya

Jat-Daaneta

Four distinct styles of embroidery — Jat-Garaasiya, Jat-Fakiraani, Jat-Haajiyaani and Jat-Daaneta — are practised by craftswomen of the Jat community. The styles take their name from the community subgroup to which the craftswomen belong.

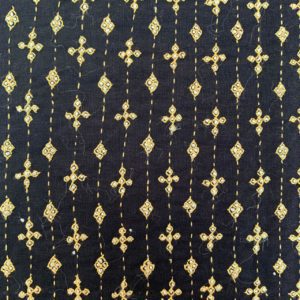

Jat-Garaasiya embroidery is geometric and resembles the mosaics found in Islamic tile work. It uses only the cross stitch and is densely rendered on thick, coarse cotton fabric. It is a counted thread embroidery style — there is no outline or drawing done on the fabric to guide the craftswomen. Instead, the design is conceptualized by counting the threads of the fabric and mentally working out the composition.

This style has a fixed number of geometric designs that are grid-based. Bold colours are used in a very specific manner in these designs. Small-sized mirrors are an integral part of this embroidery.

The embroideries of the Jat Fakiraani, Jat Haajiyaani and Jat Daaneta communities are also grid-based. They feature geometric and abstract motifs that have two unmistakable features. There is a mirror at the centre of the motifs, and there are radiating lines within the motifs and all over the composition as well.

The stitches are rendered dense and tight on thick, coarse cotton fabric. This manner of rendering the stitches gives these embroideries a solid and sturdy appearance. Mirrors lighten the denseness

Khudi-Tebha

The Haalepotra and Meghwaad Maarwaada communities practise eight styles of embroidery. They are best known for their Khudi-Tebha and Kambiro embroideries.

The origin of these two styles can be traced to the traditional practice of recycling old garments, wherein the simple running stitch was used to join pieces of fabric that still had some life left in them. So neatly and uniformly did the women embroider the functional running stitch, that over years and generations, it emerged as a decorative element with the potential to create elaborate motifs and designs. Over time, another design detail, created by using the satin stitch in silken floss, also became an integral part of these styles.

Craftswomen embroider these styles on household items; however, it is in their quilts that they showcase the most innovative expressions of the transformed running stitch. Haalepotra craftswomen have gone a step further with their innovations. Their signature quilts combine distinctive patchwork with Kambiro and Khudi-Theba embroideries.

Mukko

Meghwaad Maarwaada and Haalepotra craftswomen also embroider a variety of Pakko and Kachcho styles on their personal clothing.

The Pakko styles, such as Pakko Mukko, use a pakko stitch as the primary stitch to create the entire style or to create its main distinctive features. The Kachcho styles use a kachcho stitch as the primary stitch to create the entire style or to create its main distinctive features. Craftswomen use the term pakko, meaning strong, durable, to denote stitches that lock. The opposite of pakko is kachcho, meaning fragile. Kachcho stitches do not follow the locking principle

MUTWA

The Mutva community that lives in the remote area of Banni, at the edge of the salt desert, practises eighteen different styles of embroidery. Craftswomen refer to these individual styles as bharat. Each bharat uses only one primary stitch to create either the entire bharat or to create its main distinctive features.

For Mutva craftswomen a stitch is either a pakko stitch or a kachcho stitch. They use the term pakko, meaning strong, durable, to denote stitches that lock. The opposite of pakko is kachcho, meaning fragile. Kachcho stitches do not follow the locking principle. Nine styles use a pakko stitch as the primary stitch. These styles are referred to as Pakko bharat. The remaining nine styles use a kachcho stitch as the primary stitch and are known as Kachcho bharat.

Mutva embroidery is lush, ornamental and full of arresting details. It is known for its very tiny stitches and equally tiny mirrors. The craftswomen’s skill in working in the realm of the miniature makes the embroidery look as if it is studded with diamonds.

Mutva embroidery is also a celebration of abundance. There are thirty-four stitches, many of which have variations. There are three sizes of mirrors and nine different ways of ornamenting them. Each style is distinct and is created by using a specific stitch or stitches in a particular manner. All this makes for an embroidery universe that is infinitely vast and varied.

APPLIQUE AND PATCHWORK

Patchwork and Appliqué Patchwork and appliqué traditions exist among most communities. For many embroidery styles, master craftwork depends on keen eyesight. By middle age, women can no longer see as well and they naturally turn their skills and repertoire of patterns to patchwork, a tradition that was originally devised to make use of old fabrics.